I wrote this essay in spring 2025 for a university course on colonial Algeria. It explores the political and cultural liminality of Algerian Jews, caught between French colonialism and the rise of Algerian nationalism. Many thanks are due to my wonderful professor for an incredible syllabus and perspective-challenging debates.

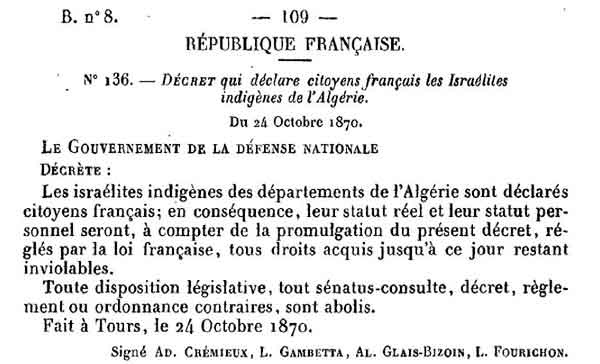

In his text A History of Algeria, historian James McDougall offers a sweeping account of Algeria’s complex sociopolitical evolution, with particular attention to the layered experiences of its minority populations. Among the most precariously positioned were Algerian Jews, who occupied a liminal space between colonizer and colonized, between French and Arab, between religious particularism and national assimilation. Though granted French citizenship en masse through the Crémieux Decree of 1870, Algerian Jews were never fully accepted by either French settlers or Muslim Algerians. McDougall reveals that their identity was less a matter of self-determination and more a terrain upon which colonial and anti-colonial ideologies clashed. McDougall uses the history of Algerian Jews to illustrate how Jewish identity became a proxy battlefield in the struggle between French assimilationist ambitions and Algerian nationalist resistance. Trapped in a web of imposed definitions, Algerian Jews found themselves perpetually alienated: too Arab to be truly French, too French to be genuinely Arab, and too Jewish to be fully accepted by either.

The tension between French expectations and Jewish self-understanding is perhaps most powerfully articulated in McDougall’s account of a Jewish man named Sasportès, who, in 1875, insisted: “French law cannot change my religious law … I never asked to become French … I am Jewish. I want to remain Jewish. That’s all there is to it” (114). This declaration cuts to the heart of the colonial misunderstanding of identity as something malleable under the pressure of legal status. French officials seemed to believe that the extension of citizenship would trigger a grateful abandonment of all previous loyalties and affiliations. For Sasportès and many others, however, French citizenship did not cancel out the centrality of Jewish identity; it only complicated it. By foregrounding Sasportès’s resistance to assimilation, McDougall highlights a foundational contradiction in France’s civilizing mission. To the French nationalist imagination, citizenship was intended to be the ultimate equalizer, erasing diversity through shared national belonging. Yet this promise could not be delivered upon for those individuals who maintained their differences. Sasportès’s desire to assume a French identity only, “for business, … so foreigners no longer abuse us,” rather than entirely abandoning his deeply-rooted Jewish identity in favor of a French one, was perceived not as a reasonable assertion of autonomy, but as a failure to be properly modern (114). This moment crystallizes the colonial arrogance of the French project: rather than accommodate pluralism, the state demanded transformation. Those who refused were labeled backwards or disloyal, distrusted and discriminated against. Sasportès’s quote becomes a voice of resistance in a sea of imposed narratives, serving as a reminder that identity is not a gift bestowed by governing powers but rather a deeply personal and historically grounded reality.

French nationalist attempts to coerce Algerian Jews to bend to their will bled over from legal and civic life into the religious and cultural fabric of Jewish communities. As McDougall notes, “In the 1850s and 1860s, locally prominent figures used the internal politics of the consistories to fight local battles over rabbinical authority, to preserve local practice against norms imposed from outside or, conversely, to press for the abolition of rituals now considered too close to ‘Arab’ (Muslim) ones, and to keep their own midrashim (religious schools), private synagogues and marriage practices” (114). The establishment of consistories, government-organized councils to manage and supervise Jewish communal affairs, served as tools of indirect control. They were tasked with “‘enlightening’ Jews and incorporating them into the citizenry that had existed in France since 1808” (114). French authorities did not need to abolish Jewish traditions directly; instead, they deputized certain local leaders to reshape them from within. This internal fragmentation speaks to the insidious success of colonial ideology. Communities that had once practiced hybrid traditions, which reflected centuries of cohabitation with Muslim neighbors, were suddenly pressured to redefine themselves according to the image of a modern French Jew. Similarities between Jewish and Muslim rituals now became liabilities. Rather than being celebrated as part of a rich regional culture, these shared practices were marked as primitive and incompatible with French modernity. This cultural cleansing was not merely administrative, as it struck at the heart of how Algerian Jews saw themselves. They were forced to make an impossible choice: conform to a French template that brought legal liberties yet devalued their history, or preserve their traditions and risk being written off as unworthy of citizenship. The result was a community internally destabilized, with its cohesion sacrificed to the demands of an assimilatory nation.

France’s so-called mission to “improve and regenerate” Algerian Jews extended systematically through consistories and organizations like the Alliance Israélite Universelle (established in 1860) and aimed to uplift and civilize a supposedly backward population. McDougall traces this ideology back to the Napoleonic Decrees of 17 March 1808, which required Jews to assume fixed surnames and temporarily banned money-lending (114). These measures, applying only to Jews in Eastern France, laid the ideological foundation for the French government’s later approach to Jewry amid the Algerian nationalist movement. What is striking is the selective nature of these policies. They were often not applied in urban centers like Paris or Bordeaux, revealing the largely performative nature of French reform. McDougall rightly critiques the unspoken assumption that Jewish assimilation into French society would occur smoothly and beneficially. In reality, the Crémieux Decree that extended citizenship to Algerian Jews also exposed them to increased scrutiny, resentment, and eventual violence. The promise of equality belied the simultaneous expectation that Jews would abandon the very practices and values that defined and sustained them. In effect, the French state did not welcome Jews as they were but invited them only on the condition that they become something else. This paradox remains key to understanding McDougall’s broader critique of colonial identity politics. The French viewed Jewish distinctiveness not as a form of cultural richness but as a deficiency to be corrected. Assimilation was not an opportunity, but a test of loyalty. The ideal French Jew was one who had erased the Arab inflections of their Judaism, adopted secular norms, and proven themselves useful to the state. In becoming that person, they forfeited solidarity with other marginalized groups and risked losing their place in the only community of which they had ever truly been an intrinsic member.

Even those Jews who did embrace French norms could not escape marginalization. As McDougall notes, “The settler anti-Semitism in Algeria… was a hatred of the Jew as an Arab” (116). This statement reveals the deep racialization of Jewish identity under French rule. No matter how thoroughly Algerian Jews Frenchified themselves, they could never shed the Orientalist projections of the European imagination. Their language, dress, and customs marked them as “Arabs of the Jewish faith,” a label that negated both their Frenchness and their Jewishness (116). Ironically, as Jews adopted French dress, lifestyles, and secular schooling, that settler resentment increased. This effect was not an accidental byproduct of colonial modernization, but a predictable outcome of a zero-sum racial order with no room for upward mobility. In the eyes of French settlers, Jews were not assimilating, they were infiltrating. The more successful they became, the more native European French viewed them as untrustworthy, cheating, and deceptively immoral. This perception, rooted in long-standing European antisemitic tropes, united with the Orientalist fear of the “Arab other” to form a particularly virulent blend of prejudice. The resulting paranoia contributed to the formation of modern antisemitism as a mass movement in France. The Algerian settler colony thus became not only a site of conflict, but a developer of harmful ideologies that would later dominate European politics. The Jews’ ambiguous status, citizens in law but not in fraternity, made them the perfect scapegoats for both French settlers and Muslim nationalists.

The culmination of this fraught history is the outbreak of violence in Constantine in 1934, when “Local newspapers[’]… anti-Jewish propaganda, … European anti-Semitic agitators[,] … local political divisions between Jewish and Muslim electorates[, and] … inflame[d] community tensions” led to deadly riots (116). As McDougall recounts, “twenty-five Jews and three Muslims were killed, and Jewish property was ransacked” (116). This moment marks a tragic turning point with the simultaneous failure of the French state to protect its Jewish citizens and the breakdown of previous Algerian Jewish-Muslim coexistence. McDougall’s decision not to elaborate on subsequent Muslim-Jewish tensions, including public reaction to the stripping of Jewish citizenship for three years (1940-1943) during Vichy rule, is telling. His choice suggests that, for the purposes of his argument, what matters most is not the continuity of conflict but rather the symbolic role Algerian Jews played in French colonial ideology. Their identity was useful to France only insofar as it demonstrated the supposed success of colonial integration. Once that narrative fell apart and Jews became targets rather than symbols, they were abandoned. The 1934 riots also exposed the limits of legal inclusion. Despite being French citizens for over six decades, Jews were still vulnerable to local political machinations and settler incitement. Citizenship could not shield them from violence. In this sense, McDougall’s narrative undermines the French Republican myth of égalité, showing that formal rights mean little without social acceptance and structural protection.

McDougall’s depiction of Algerian Jews offers a powerful condemnation of colonialism’s subversive manipulation of identity politics. He shows how Jews were drafted into a battle they never chose to fight; pressured to assimilate by the French and rejected as collaborators by Algerian nationalists, they were left with no viable path to safety or political belonging. Using the Jews of Algeria as a case study, McDougall draws attention to the true impact of holding citizenship, the violence inherent to expecting complete assimilation, and the ways marginalized groups are used as pawns amid international ideological struggles. For the French government, Jewish identity served as a field on which it sought to win its social battle over Algerian culture, before the Algerian War of Independence even began. In the case of Algeria, Jewish identity was not simply erased or suppressed, but systematically distorted to serve the competing ambitions of the French government and Algerian resistance.

Bibliography

McDougall, James. A History of Algeria. Cambridge University Press, New York, 2017.

Leave a comment